The concert series Ein menschliches Requiem draws a portrait of Brahms the man, in his Requiem, and the music of his mentor and good friend Schumann. In Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Brahms provides a new interpretation of the traditional mass for the dead. Instead of a melancholy funeral march for the deceased, the music offers strength, comfort and hope for the living. It was Brahms’ personal answer to death. The monumental composition for orchestra, soloists and choir that Ein Deutsches Requiem became stands in marked contrast sometimes to that initial objective. The version for piano duet, soloists and choir is much more intimate. Between the movements of the Requiem, there are brief piano pieces interwoven from Schumann’s Kinderszenen, as recollections of distant (childhood) days

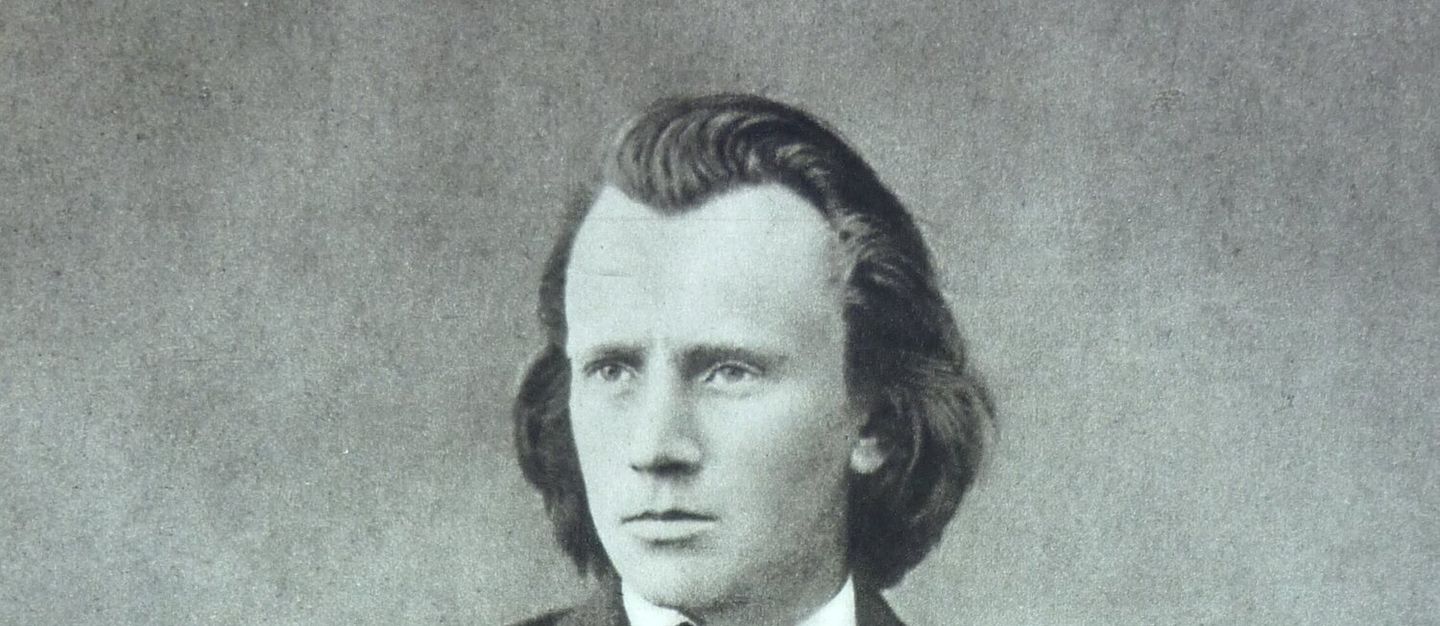

The German composer Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) was a plain and sensitive man. He stood for seriousness and tradition and valued the legacy of past generations of composers. He didn’t see the need to create new genres, but opted to update the existing genres and to apply modern, Romantic principles to existing forms; a vision that he demonstrated in all genres, from piano music to large-scale orchestral and choral works.

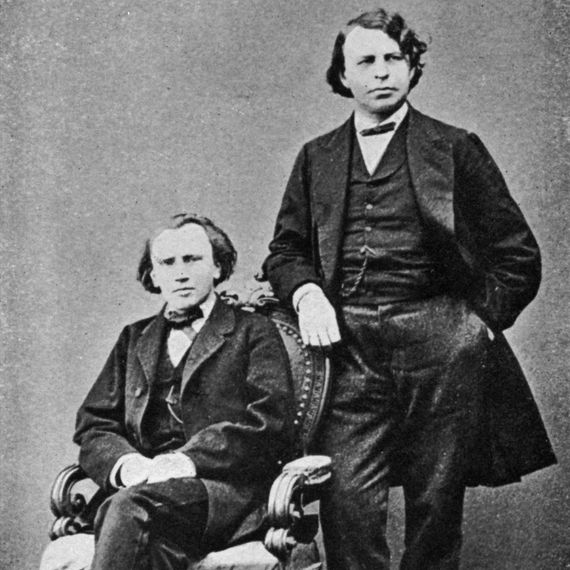

His meeting with Robert Schumann (1810-1856), another figurehead of German Romantic music had an important influence on Brahms’ career and life. Despite differences in style and aesthetic conceptions, the two composers developed a strong musical and personal bond.

“Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted.”- ein deutsches requiem

Schumann: Kinderszenen

Robert Schumann was born in Zwickau, not far from Leipzig. His father was a publisher and bookseller, and that milieu awakened Schumann’s love for literature and music. After his father’s death, the young Robert moved to Leipzig in 1826, where he enrolled to study literature. During his free time, he took piano lessons from Friedrich Wieck, the father of the talented pianist Clara Wieck – whom he would marry in 1840. Unfortunately, Schumann soon had to give up his early career as a pianist, due to physical problems with his fingers. He therefore opted for the next best thing: writing and composing. In that period, he founded the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal of Music), a publication that reported on the latest developments in German Romantic musical life. He also composed numerous short piano works, which earned him renown.One of those compositions was Kinderszenen, Opus 15, a series of thirteen lyrical character pieces for piano. In 1838, Schumann wrote around 30 piano pieces, and wrote about them to his new fiancée: “Perhaps it was an echo of what you once told me, that ‘Sometimes I seemed like a child’; in any case, I was suddenly struck by inspiration, and came up with about thirty quaint little things, of which I have selected about twelve… You will enjoy them, though you will have to forget that you are a virtuoso.” The final publication would include thirteen compositions, which Schumann initially titled Leichte Stücke (Easy Pieces). Only later did he add the current description, referring to the latter as “nothing more than delicate hints for the performance”. To this day, we can only guess whether Schumann wrote the pieces out of nostalgia for his childhood years. Despite their relative simplicity, the compositions are highly refined and poetic; some overflow with cheerfulness, others – such as the well-known Träumerei – are tender and soft.

Brahms en Schumann: an inner bond

In 1837, Schumann became engaged to Clara Wieck, but the couple would officially marry only in 1840. Clara’s father was opposed to the marriage, and launched a lawsuit in which Schumann was asked to provide evidence of his emotional and financial stability. Schumann’s mental health was indeed fragile: he suffered from depression and over the years was increasingly plagued by hallucinations and voices in his head. His mental illness reached its peak at the time when Brahms became acquainted with the Schumanns. Brahms had been struggling for some time with his status as a composer – until then, he had lived mainly from his work as a pianist and conductor – and hoped to change that by means of a letter of introduction from his friend the violinist Joseph Joachim. The visit seemed to strike just the right chord: Schumann was so impressed that on 28 October 1853 he wrote an article in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in which he proclaimed that Brahms was his successor, describing him as “predestined to give an ideal expression to his era”.

The encounter with the Schumanns provided not just a professional stimulus, but the start of a deep friendship. Brahms’ visit even helped revive Schumann and take out his pen. But in 1854, his mental health deteriorated: after a failed suicide attempt, Schumann willingly went into a sanatorium. He died there, barely three years after Brahms had played a few works for him at his home. Schumann’s death affected Brahms deeply, and it may have been one of the reasons why he composed “a sort of German requiem”. The same year, Brahms wrote down a few sketches, including part of a piano duet that he originally planned to orchestrate as a movement of a symphony. It was given the form of a funeral march, which Brahms would ultimately include as the second movement of the Requiem. In 1861, he finished a few more movements, but only after the death of his mother in 1865 did he find the time and courage to complete the work.

Ein deutsches Requiem: a human requiem

On 1 December 1867, the première of part of Brahms’ Requiem was held in Vienna: only the first three movements were performed. A few months later, the complete work was performed in the Cathedral of Bremen. But in order “to satisfy the clergy”, the aria I know that my Redeemer liveth from Haendel’s Messiah was inserted during the performance. As it happens, the administrators of the church had expressed their displeasure, at the lack of a clearly Christian message about the passion of Christ, as the performance was on Good Friday. Brahms rejected the suggestion made by the choral conductor Claus Reinthaler to adapt the text of the requiem. He had, after all, deliberately selected very specific German texts from the Old and New Testaments and the book of the Apocrypha from Luther’s Bible. Brahms thereby moved forward the tradition of Lutheran funeral music. As in Heinrich Schütz’s Muzikalische Exequien, written in 1636, the apocalyptic scenes of the Dies Irae were replaced by a more spiritual meditation on death. The verses in Ein deutsches Requiem appeal to a universal religious sentiment, and leave room for a humanistic vision – in a letter, Brahms himself added the word ‘German’ to the title in order to replace the term ‘human’. Moreover, Brahms shifted the focus of the deceased’s suffering to the survivors, who are grieving.After the performance in Bremen, Brahms added one more movement for solo soprano to after the fourth movement. He had likely already written most of this movement previously, but he could only decide on the exact placement and development of this part after hearing the entire work. The definitive seven-part structure of Ein deutsches Requiem therefore comes across as very organic. In the first three parts, the quest for consolation and the transience of human life are at the core. This is followed by a quiet passage, the high point of which is the image of the mother comforting her child in the fifth movement. After a brief dance of the dead and the triumph over death in the sixth movement, Brahms came full circle in the final movement, with the words “Selig sind die Toten” (blessed are the dead).

And so the definitive version of Ein deutsches Requiem, more than ten years in the making, had its première on 18 February 1869 at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig. It was one of Brahms’ greatest successes, fulfilling Schumann’s prediction. Soon, a version of the Requiem for piano four hands was also published. Brahms had conceived this version in January 1869, at the request of his publisher. It was common in the 19th century to publish a piano reduction of symphonic works so as to give them wider dissemination. In the transcription, Brahms kept the passages for choir and soloists intact. The message of his human requiem comes across as even clearer and more fragile in this arrangement; as a loving cloak of consolation and gratitude for what was.

Commentary by Aurélie Walschaert

Info concert

Brahms: Ein menschliches Requiem

Thursday 21 January | 20:00 | Flagey - Brusselsthis concert will take place as a livestream

Brahms: Ein menschliches Requiem

Saturday 8 January | 20:15 | Flagey - Brusselsthis concert will take place as a livestream

Brahms: Ein menschliches Requiem

Thursday 13 January | 20:15 | Sint-Pieter-en-Paulkerk - Mechelenthis concert will take place as a livestream

Brahms: Ein menschliches Requiem

Friday 14 January | 20:15 | Jezuïetenkerk - Lierthis concert will take place as a livestream

Brahms: Ein menschliches Requiem

Sunday 16 January | 15:00 | OLV van Fatimakerk - Genkthis concert will take place as a livestream

Opbrouck & Brahms

Saturday 31 January | 20:15 | CC De Mol - Liera new light on Brahms' Requiem - with actor and illustrator Wim Opbrouck

Opbrouck & Brahms

Sunday 1 February | 15:00 | Theater Heerlen - Heerlen (NL)a new light on Brahms' Requiem - with actor and illustrator Wim Opbrouck

Opbrouck & Brahms

Tuesday 3 February | 20:00 | CC Den Amer - Diesta new light on Brahms' Requiem - with actor and illustrator Wim Opbrouck

Opbrouck & Brahms

Wednesday 4 February | 20:15 | TivoliVredenburg - Utrecht (NL)a new light on Brahms' Requiem - with actor and illustrator Wim Opbrouck

Opbrouck & Brahms

Saturday 7 February | 20:15 | Het Perron - Iepera new light on Brahms' Requiem - with actor and illustrator Wim Opbrouck