Suffering at the cross

The cantata cycle Membra Jesu Nostri patientis sanctissima – today often abbreviated to Membra Jesu Nostri – is one of the most famous works by Dietrich Buxtehude (ca. 1637 – 1707). Nowadays it is frequently performed in passion time, as an alternative for the St. John or St. Matthew Passion. The Danish-German composer, organ player and music teacher spent the majority of his life in the German city Lübeck. There he worked as organist of the Marienkirche, composing a plethora of organ and harpsichord pieces as well as religious vocal music.

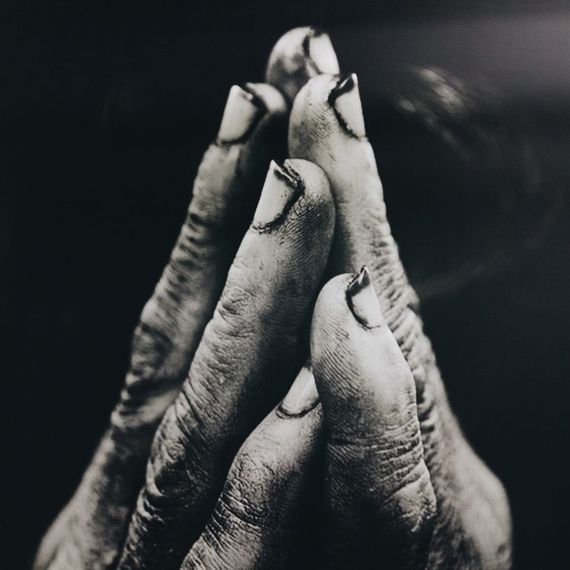

Buxtehude’s Membra Jesu Nostri consists of seven cantatas, each contemplating the limbs of the crucified Christ – his pierced feet, bent knees, bleeding hands, wounded side, revered breast, loving heart, and thorn-crowned face. The texts are based on the medieval passion hymns Salve mundi, salutare, in their turn based on the mystical meditations of Arnulf of Leuven. To each of these poems, Buxtehude added a fitting biblical quote. For each movement he chose a concertante setting in which the choir and instrumentalists work together, followed by hymne stanzas shaped as solistic arias. Each cantata thus opens with an instrumental introduction, after which choir and soloists alternate.

Remarkably, in one of the biblical quotes chosen by Buxtehude he refers indirectly to the theme of the motherly comfort. For the fifth cantata Ad Pectus he chose a fragment from the first Peter letter referring to the newborns craving milk, a metaphor for the yearning for divine – of female – comfort. That atmosphere of safety and familiarity is expressed by Buxtehude by the absence of the two highest female voices.

Also in the other movements of the cycle, Buxtehude manages to translate the sensual texts to very evocative music. The poignant, sometimes wistful dissonants lead to Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710-1736) and his famous Stabat Mater. “The grieving Mother stood weeping beside the cross where her Son was hanging.” This is the first line of the poem written around 1300 in honour of Holy Mary, used by Pergolesi when he composed a new Stabat Mater at the end of his life. The work was commissioned by Neapolitan brotherhood ‘Cavalieri della Virgine de Dolori’ who wanted to replace Alessandro Scarlatti’s version of the Stabat Mater, which they always used at their private worship on Good Friday. This fact explains the intimate setting and atmosphere of this vocal chamber music work, that reflects on the suffering of Christ from the motherly point of view.

A modern response

With her Ad Genua Icelandic composer Anna Þorvaldsdóttir (1977) created a response to the second cantata, addressing the knees and lead by the poem of her regular lyricist Guðrún Eva Minervudóttir: “Guðrún Eva Minervudottir’s beautiful text inspired the lyricism of the solo voice that planted the seeds for the music. The music is also inspired by the notions of humility and of turning a blind eye - and a sense of longing for beauty in the face of pain and difficulty. The music envelops the solo voices in a dreamlike state, both terrifying and calm at the same time.” The result is an ethereal and accessible work, offering a moment of gentleness and contemplation.

The American Caroline Shaw (1982) is a New York-based musician — vocalist, violinist, composer, and producer — and the youngest recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2013 for Partita for 8 Voices, written for the Grammy-winning Roomful of Teeth, of which she is a member. Her composing for choir stems in her love for the voice and the conviction to bring people together in important matters. To the Hands unites these ideas in a suite of six short chorals on her own lyrics. In both her musical language as well her texts Shaw blends old and new, the past and the present: “To the Hands inside the 17th century sound of Buxtehude. It expands and colors and breaks this language, as the piece’s core considerations, of the suffering of those around the world seeking refuge, and of our role and responsibility in these global and local crises, gradually come into focus.”

Meditation on death

With Buxtehude’s lament from the cantata Fried und Freudenreiche Hinfahrt from 1674 we come full circle. The cantata consists of two parts: the first – a choral setting of Martin Luther’s Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin in fourt part invertible counterpoint – he had already composed in 1671 on the occassion of the funeral of the head of the church in Lübeck, Meno Hanneken. The second lament he composed after the death of his father. In the text – presumably written by Buxtehude himself – the author is in search of enlightenment for his suffering in memories and in the unification of the deceased an the divine. That eternal human longing for unity for god is the common thread throughout the closing composition of the mystical American composer Patricia van Ness, also known as a modern Hildegard von Bingen.