More than a Norwegian fairy tale

Henrik Ibsen wrote Peer Gynt in 1867 based on a tale from Gudbrandsdal. In the original story, Peer is a hunter who saves three dairy-maids from the hands of trolls. Ibsen opens his play as a Norwegian fairy tale, but takes his hero Peer Gynt far away from Europe. Along the way, it becomes clear that Ibsen intended to do more than tell a Norwegian story or a satire of the legendary Norwegian self-satisfaction. Peer Gynt is a play about human existence, a modernized Everyman in search of salvation.

Peer Gynt was first performed in 1876 in the theatre of Christiania, as Oslo was then known. Ibsen had asked Grieg in 1874 to write music for the performance. Grieg admitted that the subject gave him many a headache. He was also given strict time limits for each piece. The music had to set the right tone from the outset.

Wastrel and liar

Peer Gynt is the son of van Jon Gynt. Because his father squandered all his money, Peer’s mother Aase places all her hope in her son. But in vain, since Peer is a wastrel and a liar. Aase accuses him of having spoiled his chances to win the hand of the wealthy Ingrid. At her wedding, he is mocked for having to watch his rival, Mads Moen, marry Ingrid. Peer meets Solveig, the daughter of an immigrant family. While drunk, Peer conceives a plan to kidnap Ingrid. But he deserts her immediately because his heart belonged to Solveig. The dark elegy Ingrid’s Lament depicts her sorrow. Out of shame, Peer was exiled from the city. In the mountains, he meets three young maidens waiting for trolls. Peer had some fun with them. A woman in green took him along to the troll king. In the Hall of the Mountain King represents the ordinary folk he met there: gnomes, trolls and underworldly spirits.

Peer is given an offer to turn into a troll and marry the king’s daughter. For Ibsen, the troll is a symbol of unbridled selfishness. Whereas people say ‘be yourself’, the trolls say ‘stand up only for yourself’. Peer escapes time, but seems to have begotten a child in his mind.

Peer meets the Bøyg, which literally means ‘the curve‘, and let himself be persuaded to stick to the easiest path. When Solveig leads him into the mountains, determined to stay with him, Peer nevertheless opts for the path of least resistance. His hideous troll son follows him. Peer cannot handle the situation and follows the Bøyg’s advice. He visits his dying mother one last time. In his imagination, he takes her one last time – to the tune of Grieg’s Aase’s Death – to a fabulous feast at Soria Mora castle, where Saint Peter welcomes her.

Further away than home

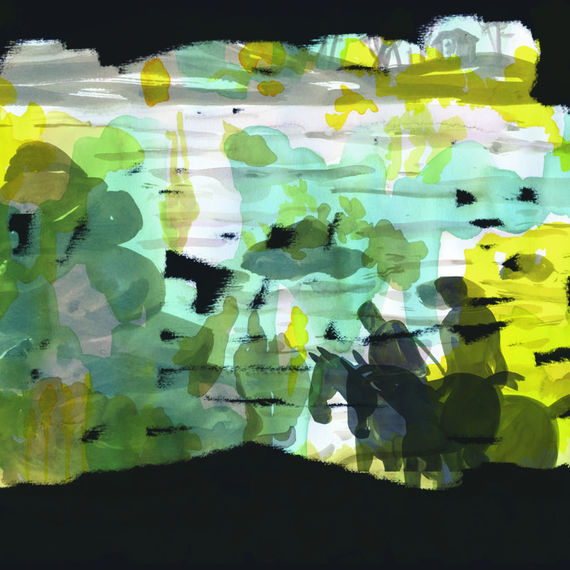

Peer is living in Africa, engaging in trade, including of slaves. The music of the Morning Mood describes a sunrise above the desert. A thief and a receiver have stolen the emperor’s horse and robes. They flee as soon as they see the emperor’s knights approach. Peer passes himself off as a prophet. Anitra and a group of Arab women sing and dance for him. Anitra seduces him with the sensual notes of Anitra’s dance, only to steal his money and then vanish.

The story returns to Norway, to the tune of Peer Gynt’s Homecoming, for a single image: in Solveig’s Song, Solveig – now middle aged – sings while spinning about how throughout the seasons, she waits for Peer’s return. She is determined to meet him again, in this world or the next.

Peer is in Egypt, passing by the statue of Memnon. At the pyramids, he addresses the sphinx, believing it to be the Bøyg. A madman takes him along to an asylum. The madness he sees there is nothing but a radical consequence of trolls’ morality: living for oneself. The insane honour Peer as the emperor of the self.

Peer returns to Norway, during the melody of Peer Gynt’s Homecoming, as an embittered old man. A shipwreck (to a fragment of the same name in Grieg’s score) in which he allowed another person to drown in order to save himself, throws him onto the beach. At an auction, he sells everything that came from his previous life.

Forgiveness

It is the evening before Pentecost. In the hut, he hears Solveig singing. He doesn’t dare go inside. The Bøyg in him tells him to keep on avoiding the problem. To the tune of Grieg’s Night Scene, Peer is confronted by everything he has left undone in his life. With a subtle reprise of Grieg’s Aase’s Death, the voice of his mother accuses him of having cheated her even on her final journey.

Through the heather, he comes across a strange person whom he takes for a gravedigger. The man reveals that he is a button caster. God gave him the task of colleting the souls of people who were nobodies, and to melt them down for reuse. Peer wants to prove that he was someone. He asks for help from the troll king and the devil. The troll king declares that he is not a human being but a troll. Even the devil (‘the Lean One’) says that he cannot go to hell because he has not committed any real sins. Peer now understands that he was a nobody. From his hut, he hears Solveig singing again. The button caster keeps on asking him for the list of his sins. Desperate, Peer goes inside the hut and asks for Solveig’s forgiveness, who is now old and nearly blind. She replies that she has nothing to forgive him for. He asks her: where was I the person I was supposed to be?

She replies: in my faith, my hope and my love. Peer buries his head in her lap. Solveig sings a cradle song for Peer. The button caster is waiting around the corner: ‘We’ll see each other again at the crossroad. Then we’ll see … I won’t say anything more.’

Written by Francis Maes