What lies beyond our cosmic horizon that gave rise to the flickering primordial heat? What lit the fire that set our universe going in the first place? These are profound unanswered questions. These are also the questions which lie behind much of my work with Stephen Hawking. And it seems we are in good company. In the next work, The Unanswered Question, Charles Ives too asks the perennial questions of existence.

Now I would like to point out that questions about our ultimate origins did not even exist as scientific questions before Einstein. They only crystallized during the 20th century once Einstein had anchored space and time, and the cosmos as a whole, as physical concepts within the sciences.

You may wonder why E himself didn’t provide the answer. After all, he was smart, and he had a new theory. Well, E’s theory of relativity can take us somewhat beyond our cosmic horizon here, but not very much. This is because beyond this horizon lies the big bang, the beginning of our world, where our basic notion of reality in terms of space and time ceases to have any meaning. One could say that “The beginning of the world happened a little before the beginning of space and time”. But this is bad news for E, since without space and time he has no theory. E’s theory has the truly remarkable property that it predicts its own downfall, in a big bang at the origin of time, which itself remains shrouded in mystery.

At the big bang, the large cosmos merges in a sense with the micro world of particles and atoms; E’s relativity clashes with the quantum theory that describes the microscopic world. The BB is in many ways the ultimate Q lab. We now believe that these tiny flickers in the afterglow of the big bang, the seeds of you and me, arose from quantum uncertainty at the birth of our universe. In fact Hawking and I found that even our entire universe bears traces of the quantum fuzziness at its origin. From the same beginning widely different universes emerge, and the cosmos lives them all. The multiverse is essentially an unavoidable consequence of our quantum origins.

But not all universes are habitable. In fact our universe appears to be very special in this respect. The temperature variations we see here, for instance, were just right to evolve over millions and billions of years into galaxies, stars and planets, thus creating a stable habitat for life to emerge. If the primordial variations had been a tiny bit larger there would only be black holes. If they had been slightly smaller, our universe would be nothing but a vast void. Our universe is mysteriously suited for life; it set out on a delicate habitable path. These insights emphasize the profound reality that we are connected to the cosmos. Not just in trivial ways, but in the deepest possible ways. We co-evolved with the universe. The cosmos is also about us, about who we are.

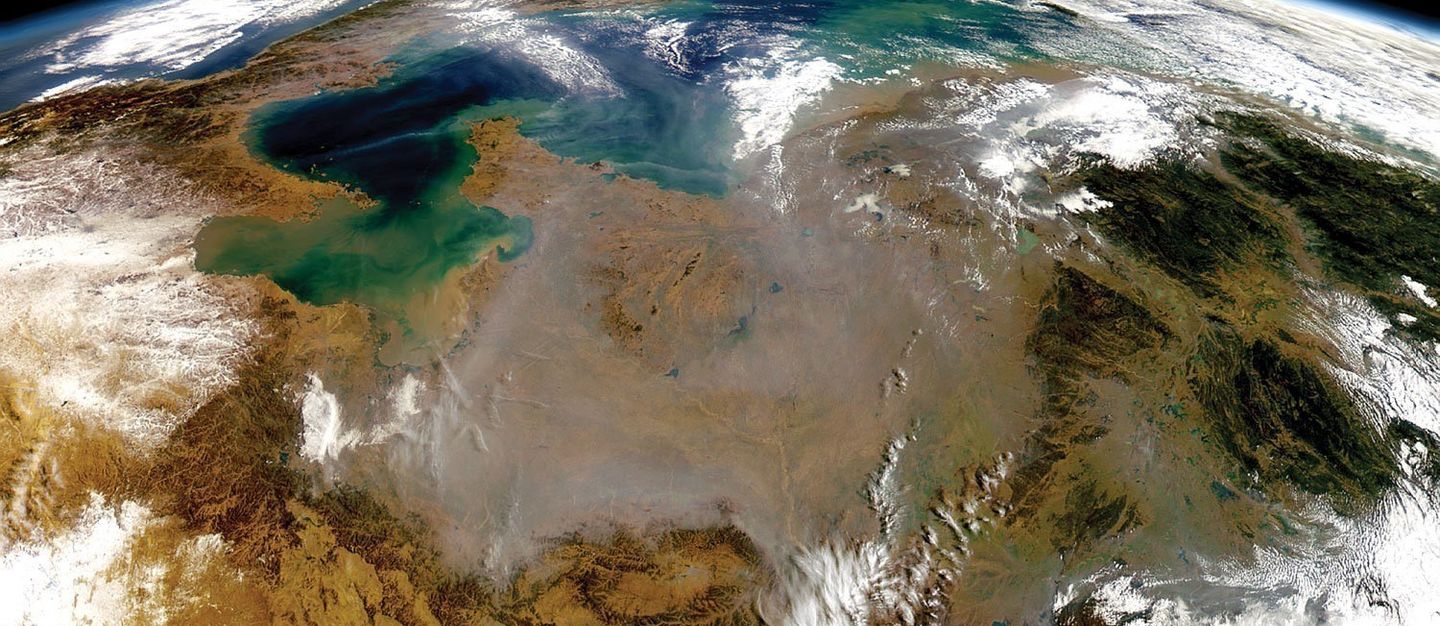

This resonates with one of the great revelations of the space age, namely the perspective that it has given humanity on ourselves.

We thought the Apollo missions were taking us into space, but when the crew of Apollo 11 turned the camera around to photograph the Earth, we realized we were in space already. When we see the Earth from space we see ourselves as a whole; we see the unity and not our divisions. One planet, one human race. A blue dot in a special, delicately habitable cosmos. Let us strive to turn this sense of belonging into an asset for humanity when over the next decades we take into our own hands the future destiny of our planet. Understanding the order of the universe and understanding its purpose are not identical, but they may not be very far apart.